Stories from a drowned land

Alumna Phaedra Haringsma talks to us about her family history and what inspired her to investigate colonial wrongdoing in Suriname

A conversation in her grandparent’s kitchen led Phaedra Haringsma (MSc International Relations 2022) to investigate the impact of the Afobaka Dam on Suriname’s rainforest populations. Phaedra describes her family’s history, researching colonialism at LSE, and her decision to investigate the land that her grandfather helped drown.

How did your family come to emigrate to Holland?

"My family history is deeply intertwined with Dutch colonial history. My ancestors from my mother’s side were trafficked from West Africa to the Dutch colony of Suriname during the Atlantic Slave Trade era. There they worked as enslaved and indentured labourers on plantations until 1873.

In 1970, when my mother was a toddler, her family emigrated to the Netherlands. The Surinamese road to independence, which happened in 1975, was rocky. More than a third of the Surinamese population emigrated in the 1970s as it was only by relocating to the Netherlands that they could keep their Dutch citizenship.

My father, however, was born in Singapore to a Dutch family. My grandmother was Dutch but moved to Indonesia during World War II to be close to her brother. She eventually met my grandfather, who was a captain on commercial ships, and they settled in Singapore before returning to the Netherlands in 1962.

My parents met in the 1980s at the University of Amsterdam’s law school. I’ve always found Amsterdam a great place to grow up in — small, safe, beautiful and easy to navigate. However, as a teenager I became aware of the legacy of Dutch colonialism, its ramifications for the society I was growing up in, and the ways in which this influenced my personal life."

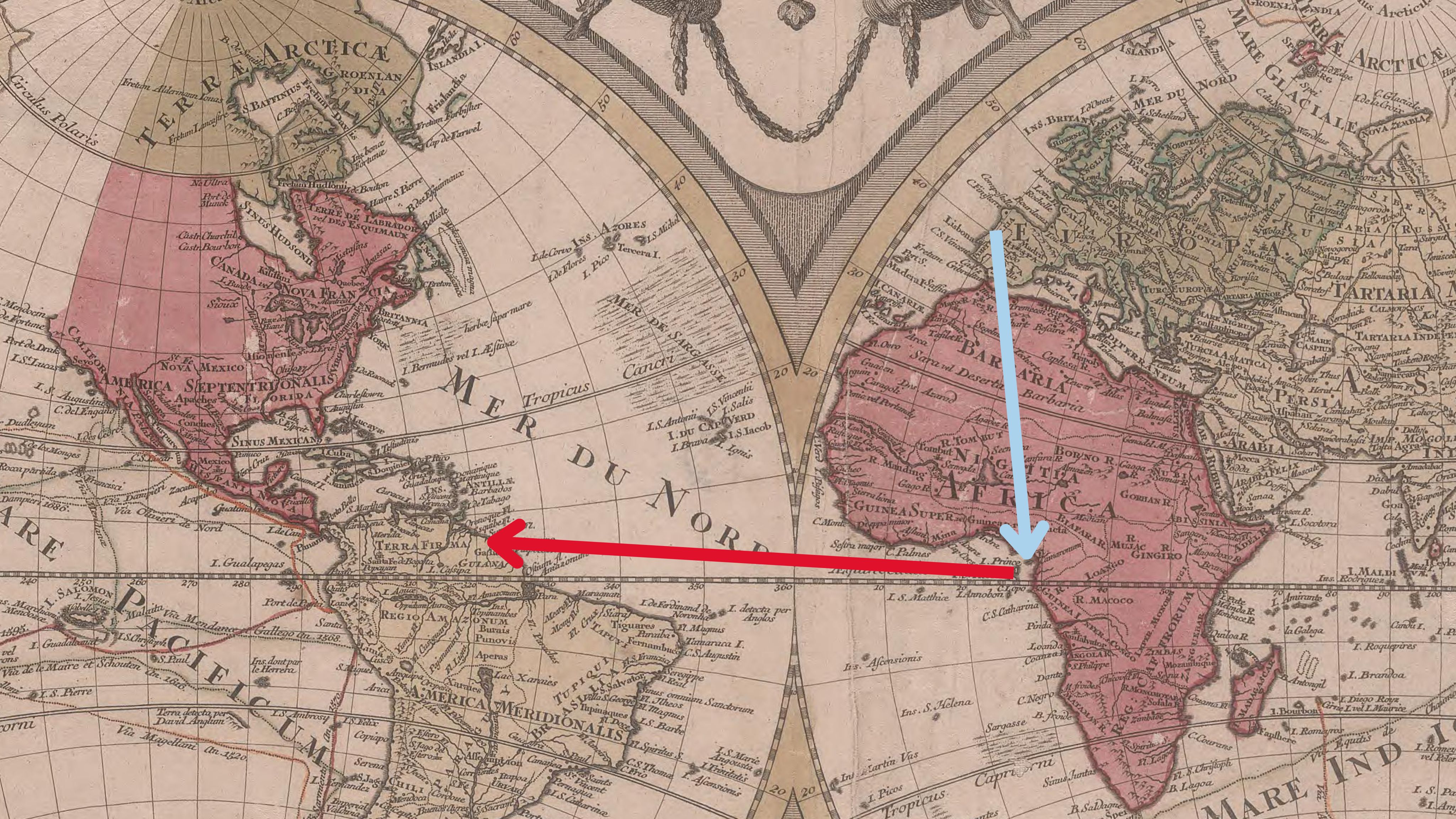

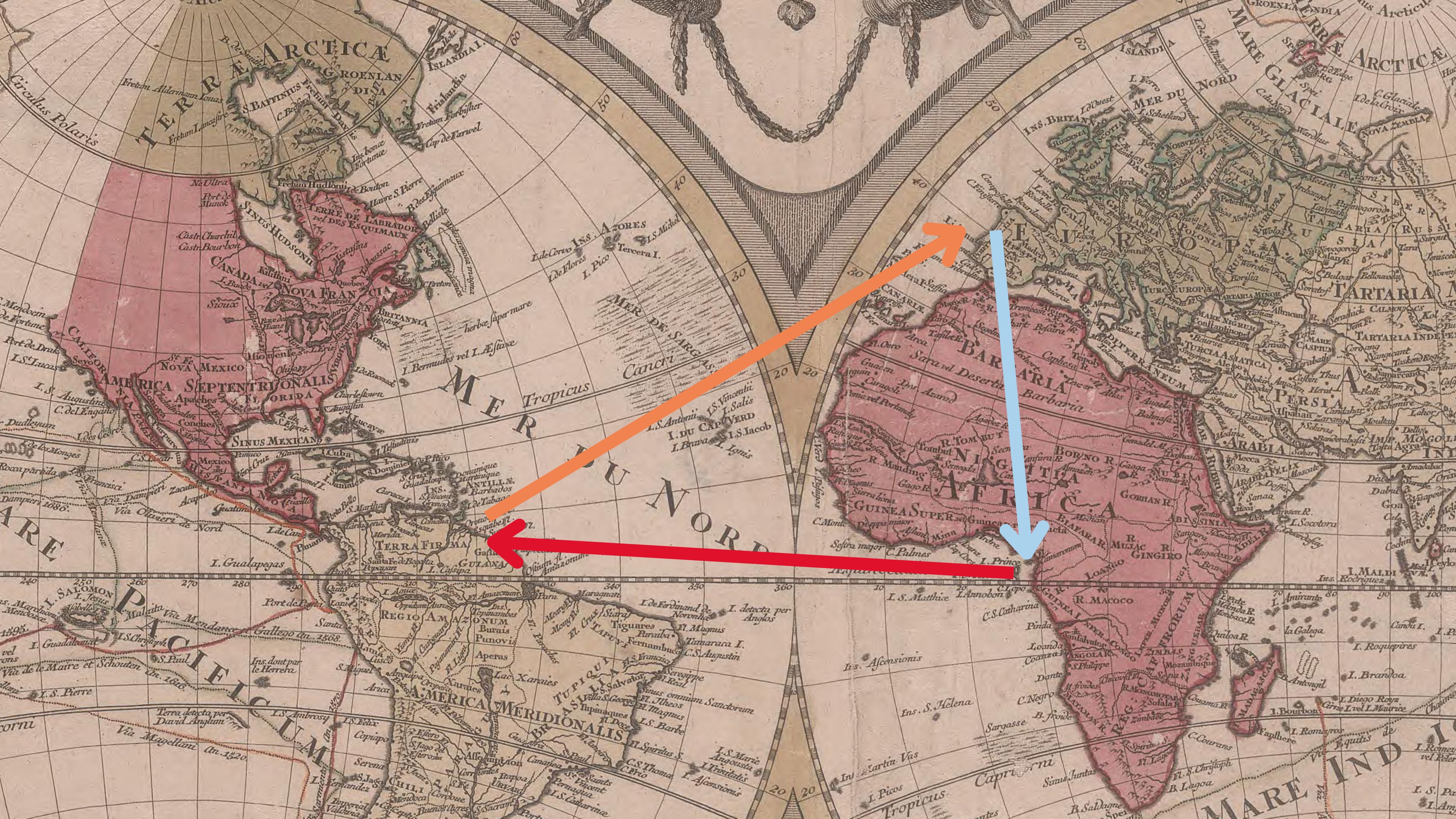

An estimated 200,000 West Africans were trafficked to Suriname from the 1600s to 1800s as part of a triangular economy. This extracted raw resources from the Americas to Europe. In Suriname conditions for those enslaved were so bad that the population struggled to grow, despite the constant importation of people.

The movement of enslaved Africans to the Americas was called the Middle Passage.

Manufactured products such as textiles, guns and alcohol were transported from Europe to the nations of West Africa.

Europeans exchanged these goods for enslaved Africans who were then brought to the Americas to work on plantations.

Treatment on the slave ships were so poor many did not survive the journey.

The coffee, sugar, cotton and tobacco produced by enslaved people on the plantations were then transported to Europe for manufacturing or consumption.

In Suriname coffee and sugar dominated the plantation industry.

The extractive nature of this colonial economy meant that inequalities remained entrenched in Suriname into the twentieth century. When Suriname began to move to independence in the 1960s and 1970s, it did so without offering the people a referendum. While part of the Dutch empire, Surinamese people had Dutch citizenship. This caused a rush to emigrate before independence severed that arrangement.

At the same time Suriname was rich in natural resources which meant that large US companies, such as Shell and ALCOA (Aluminium Company of America), operated subsidiaries in the area.

What led you to study at LSE?

"I decided to study international relations at LSE, where I had the freedom to tailor the programme to my interests. I was doing a part-time masters, which allowed me to enjoy all the readings and books assigned. One of my favourite memories was studying at the top floor of the Centre Building, watching London under the setting sun. Another one was finding a rare document in the National Archive of Suriname, where I conducted some archival research for my dissertation.

I lived in London at a strange time for it was just opening up after COVID-19. I enjoyed spending time with my friends, both old and new, and exploring the nightlife. Amsterdam is a very segregated city, but in London I found nightlife to be much more diverse. During my time at LSE I wrote two blogs, one a winning entry in the student writing competition Black Forgotten Heroes, and the other one a book review on the first English translation of De Kom’s seminal work We Slaves of Suriname.

I also spent my time in London on some of my own projects. I wrote an essay for the Amsterdam-based community archive The Black Archives, about inequalities between Caribbean and European Dutch citizens, spending six weeks in the Caribbean island of Bonaire to research the essay."

"My courses at LSE helped me think about colonial history and global inequalities in a more nuanced and structured manner. I followed courses like China and the Global South, Economic History of Colonialism, Empire and Conflict in World Politics, and Politics of Inequality and Development. However, these courses mostly focused on British and French imperialism. The Dutch Empire was never discussed. This motivated me to write my dissertation on the Dutch-speaking anti-colonial and anti-capitalist revolutionaries Anton de Kom and Hermina and Otto Huiswoud. Their ideas about global equality and solidarity have been largely forgotten or have never available in the English language.

This laid the foundations of a journalistic career where I write about forms of neo-colonialism, mostly in the Netherlands and Suriname, so in this sense, my studies at LSE prepared me for this career path. "

And the system worked. No better way to foster a sense of inferiority in a race than through this form of historical education, in which the sons of a different people are the only ones mentioned or praised. It took a long time before I could free myself entirely from the obsessive belief that a Negro is always and unreservedly inferior to any white.

Anton de Kom, We Slaves of Suriname, 1934

How did your research into the into the impact of the Afobaka dam begin?

"My latest journalistic project began in my grandparents’ kitchen in 2020, amidst my time at LSE. My grandmother had passed away earlier that year, and I was in Amsterdam for the Christmas holidays. I spoke with my grandfather, Johan Henrij Dumfries, about his life in Suriname and his time working for the Surinamese colonial government. He was born on the sugar plantation where our ancestors had been enslaved and grew up poor in Paramaribo, Suriname’s capital. However, this government job catapulted him into a lifestyle he could only have dreamed of in his youth.

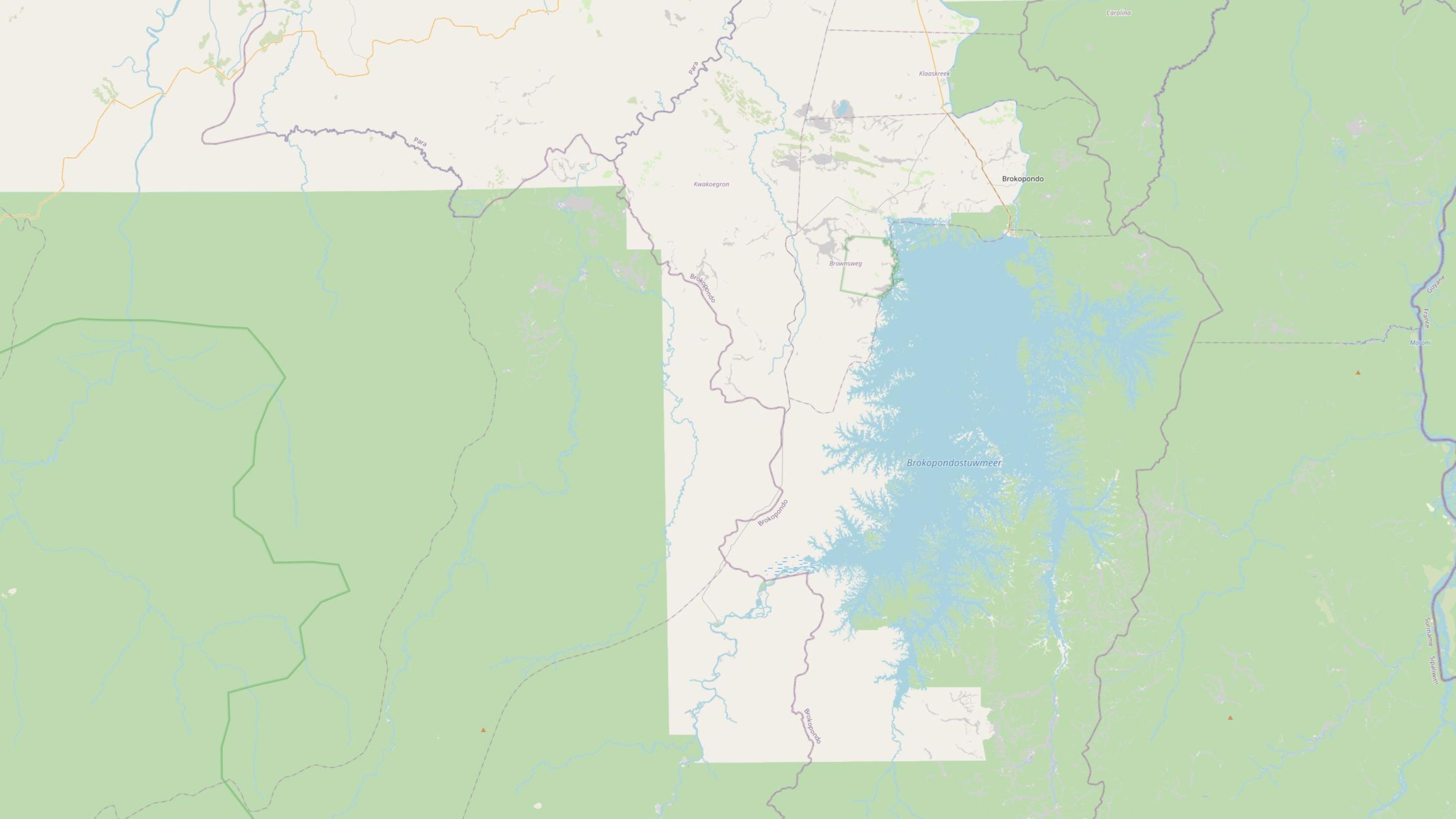

At the same time, he also felt a deep sense of regret. The team he worked for was responsible for displacing the Maroon population. They are the descendants of the people who escaped slavery and formed their own communities. The Surinamese government was developing a hydroelectric dam which would provide energy for the smelter belonging to the American aluminum producer, ALCOA. The Afobaka dam created a reservoir which would flood the lands of the Saamaka and Okanisi Maroon people. The government displaced them, making promises about compensation and infrastructure that ultimately proved false. Many still live in the "temporary" housing provided in 1964, their communities torn apart by the displacement."

The Brokopondo region of Suriname in (c) 1914, before the building of the Afobaka dam

The Brokopondo region of Suriname today showing the vast area of land submerged by the Afobaka dam.

Until now, in Suriname, bauxite was only purified of impurities and then shipped in large quantities. With the construction of the massive Afobaka dam and its associated hydroelectric power plant, that has changed. Behind this dam, a reservoir has formed as large as the province of Utrecht.

Dam and bauxite mining in Suriname, Dutch news reel 1965

Every now and then I still sit there and cry in that chair when I think about it. If I were asked to do it again today, I would say a loud, 'NO!'

Johan Henrij Dumfries

How did inequality in Suriname become so entrenched?

"The root cause of the ongoing threats to indigenous and tribal populations in Suriname is their complete lack of land rights. At any moment, the Surinamese government can grant a concession to a corporation or even an individual, allowing them to exploit the land.

This means that someone can come the next day and destroy the land and livelihoods of the local population. Suriname is incredibly rich - gold, timber, oil, diamonds, and bauxite - but those reaping the benefits from this vast natural wealth are Chinese, Canadian, American and French multinationals, and a few members of the Surinamese elite, mainly based in Paramaribo.

Despite Suriname’s independence, the colonial structures never disappeared. For indigenous and tribal communities, the nationality of those stealing their lands and poisoning their rivers — whether Dutch, French, Chinese, Brazilian, or Surinamese — makes little difference. The fundamental issue remains the same: without land rights, they are left powerless. In 2007 the Inter-American Court of Human Rights found Suriname guilty of violating these rights. It is only now, 18 years later, that Suriname's leadership has promised to correct this wrong. Securing these rights is the first and most crucial step towards a more just and prosperous future. If Suriname’s natural wealth is to be extracted, the primary beneficiaries should be the indigenous and tribal populations themselves.

The global community, including anyone reading this interview, must actively support the indigenous and tribal resistance against logging and mining. Educate yourself on these issues, raise awareness by sharing information, and consider donating to organisations that aid these communities."

The residents of the area were told: we are building a reservoir to generate electricity, so you will get free electricity.

Johan Henrij Dumfries

The government was ordered by the whites to build the dam. And again we were sold by our own people for a lot of money.

Hesdy Kadosoe, Brokopondo resident

They simply stole the land from us.

Agbagó Aboikoni, Saamaka Chief

How do you hope to create positive change for Suriname's people?

"I hope that my reporting shifts perceptions of Suriname’s indigenous and tribal populations. For a long time, they have been regarded by the country’s elite — both Surinamese and Dutch — as "primitive" or "backwards". In my work, I try not only to highlight the injustice of what happened in Brokopondo, but also the pride and resilience of the people. The Maroons are among the true heroes of Surinamese history, resisting not only physical slavery by escaping the plantations and defending their freedom, but also mental slavery by preserving and developing their own cultures and societies.

As a journalist, I like to combine oral history, through audio recordings and poetry, with traditional reporting, archival research, and photography. Text alone is not always the best medium to convey the depth of these stories. What began as a series of five articles has now evolved into a book. In this story collection Verdronken Vrijheid (A Freedom Drowned), I combine oral history, archival research, photography, and poetry — written by Saamaka spoken-word artist Noris Bannafoo — with a translation into Sranantongo by Denise Jannah. This multidisciplinary approach allows for a richer, more immersive account of the histories and experiences of the communities affected.

My article on Bonaire prompted parliamentary questions directed at the Dutch Minister for Poverty Policy, Participation, and Pensions. I hope that my book will awaken policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic and will usher in improvements in the lives of the people of Suriname."

Phaedra Haringsma

MSc International Relations 2022

If you are interested in reading Verdronken Vrijheid (A Freedom Drowned), please email Phaedra.

Explore more alumni stories

Making a difference back home

"It was time for us in our institutions to reflect what we were rather than what somebody else wanted us to look like."

Retired Chief Justice Sir David Simmons looks back on a life lived during a pivotal moment in Barbadian history.

Healing through writing

"I think it's essential for all of us who come from refugee backgrounds to know our stories."

Christina Vo looks back on her family story. What inspired her to return to the country that her father fled from, and why did she decide to write her memoirs?

The stories that go unheard

"I wanted to provide the support that I wished had been available to me."

Alex Sangha discusses his experiences as a gay South Asian Canadian and LGBTQ+ rights advocate and what inspired him to set up Sher Vancouver.